Understanding the importance of airline partnerships to redeeming your points for maximum value is essential, so I wanted to go over the different kinds of partnerships airlines may have in this post.

- Why you should care

- Interline agreements

- Codeshare agreements

- Joint ventures

- How do alliances fit into this?

- Are there other forms of partnerships?

- Summary

Why you should care

An example: It seems intuitive that you would redeem Delta SkyMiles for a Delta Airlines flight, right?

Actually, it couldn’t be further from the truth. The best value usually comes from redemption opportunities through the frequent flyer program of a partner airline. For Delta, one option is Virgin Atlantic. For example:

As you can see, Delta flight DL46 in economy class on 4/23/2025 is 62,000 points (+ $5.60 in fees) through Delta SkyMiles, yet it is only 30,000 points (+ $5.60 in fees) through Virgin Atlantic. That is a major difference!

There are many such ‘sweet spots’ with frequent flyer programs to redeem points with partners. The implication is that it’s common to strategically accumulate points in frequent flyer programs of an airline you have no interest in flying. But I will discuss this strategy in another post.

Truthfully, prices can be similar across frequent flyer programs, but that’s why it’s essential to do your research. Don’t just look at the redemption opportunities through the frequent flyer program of the airline you want to fly, but also look at opportunities through the frequent flyer programs of its partners, since great value can often be found there. That is why you should care about airline partnerships.

Interline agreements

The interline agreement is the simplest agreement, and allows multiple airlines to be included on a single ticket. It means that bags can be checked through to the final destination and one doesn’t need to check-in at when transferring. In terms of loyalty perk reciprocity, you should not necessarily expect any. It’s very common for airlines to have these agreements, even as competitors. It allows them to ticket passengers onto each other’s flights in case of operational issues. For example, see below for Delta’s interline partners, and you will see it includes competitors, such as United Airlines (UA).

Codeshare agreements

A step up from interline agreements are codeshare agreements. These allow airlines to not just ticket multiple airlines on the same ticket, but also market them as if they are their own flights and assign those partner flights their own flight numbers.

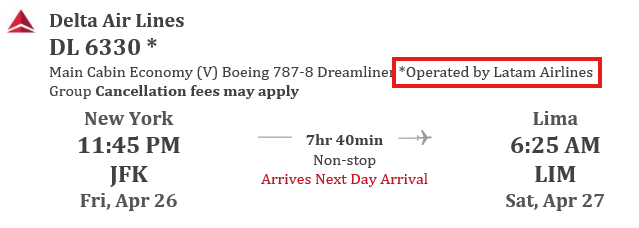

How can you recognize a codeshare? Look at the below example from a flight my husband and I booked with Delta to Lima, Peru last April: you see the Delta flight number DL6330, but it also says ‘operated by LATAM’, which is what signifies this as a codeshare. Delta is marketing the LATAM flight as if it’s a flight it operates itself, but it’s a LATAM flight. The LATAM flight number for this flight was LA2469.

So, how does this help passengers more than the interline agreement? What I found is that if airlines can market each other’s flights as if it’s their own, they are much more likely to offer them to their customers, because the airline will receive a cut. As such, codeshares can significantly expand an airline’s route network, providing additional options for its customers. However, you can also argue that codeshares are less transparent for passengers, since those that are not aware of these constructions may find themselves on an airline that they didn’t expect.

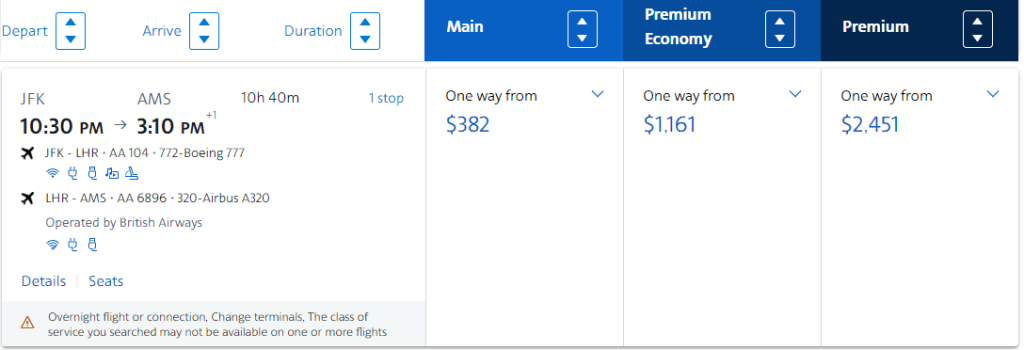

On the other hand, if you’re savy and you know your partnerships, you can also ‘manipulate’ this to your advantage. For example, American Airlines does not fly to Amsterdam, but through a codeshare agreement with British Airways, they can ‘operate to Amsterdam’ with one stop:

As you can see, American flies to London on AA104, from where British Airways then flies to Amsterdam as AA6896, all on a single ticket, issued by American Airlines with AA flight numbers. I personally took advantage of this a while ago since I had to use an American Airlines voucher, but did not want to fly American. Thus, I purchased a ticket with American that was operated by British Airways.

Joint ventures

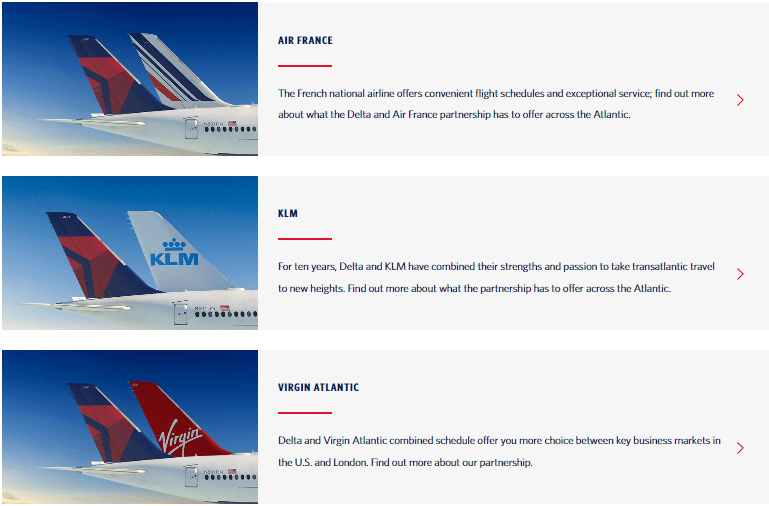

Joint ventures are the closest partnership between airlines, and are typically specified around a set of routes (e.g. transatlantic, or transpacific). Here, airlines don’t just make transfers logistically easier and market each other flights, they also coordinate schedules and prices. Essentially they operate as a single entity on those routes. An example is the transatlantic alliance between Delta, KLM, Air France and Virgin Atlantic (and perhaps soon to be joined by SAS).

This can be tremendously helpful for passengers, because if the schedules are coordinated, it significantly improves connection times at transfer airports. Thus, flying from New York-JFK to Milan via Paris, with NYC-CDG on Delta and CDG-LIN on Air France, will ensure a short connection time of 1-3 hours in Paris, rather an 8+-hour layover, thanks in large part due to the joint venture.

However, such tight cooperation comes with regulatory hurdles that need to be cleared. Governments need to ascertain that the joint venture doesn’t harm the overall competitive landscape, and that reliable service will still be provided for reasonable fares. That may sometimes mean that governments stipulate that operation privileges at airports (slots) are given up, so as to provide equal access of passengers to competitors.

How do alliances fit into this?

Alliances are a different beast. There are three big airline alliances: OneWorld, SkyTeam and Star Alliance.

People assume that airlines that are part of the same alliance cooperate extensively, but this isn’t necessarily the case: airlines may just have interline agreements. For example, it’s only after many years of being SkyTeam members that Delta and Saudia are engaging in a just-announced codeshare. It seems they only had an interline agreement, despite being in the same alliance.

So, if the level of cooperation between airlines in an alliance can be patchy, what’s the alliance’s benefit for passenger? I find that it’s all about the standardization of frequent flyer perks across members, enhancing predictability of services and lounges. This is achieved by mapping frequent flyer status tiers from individual airlines to a ‘universal’ alliance tier, that governs what perks a passenger should be getting. For example, the Silver tier in the Delta SkyMiles and Air/France Flying Blue programs both map to the SkyTeam ‘Elite’ Status, for which the benefits you can see below:

Reciprocal status perks will be given regardless of whether the airline that ‘gave’ you alliance status (e.g. Delta SkyMiles), and the operating alliance partner (e.g. Garuda Indonesia), have any kind of formal cooperation. Thus, if you had been a SkyMiles Silver member, you would have had SkyTeam Elite status, and would have been able to get the related perks on Garuda Indonesia – codeshare or not. This also means that once you have status with an alliance, it’s attractive to keep flying with members of that alliance, so that your status can be of use. I’d argue this is a perk for airlines: it’s a way to establish consumer loyalty and can direct business to them when otherwise there would have been a near-zero chance of a passenger flying that airline (such as with Delta passengers flying Saudia).

A more in-depth comparison of the ‘big three’ alliances will be the subject of a follow-up post.

Are there other forms of partnerships?

The above is not all there is. If we continue with the Delta examples, this is an airline that has established financial stakes in multiple airlines. LATAM is one of those, which is the reason why it left it’s original alliance (OneWorld). Thus, Delta established a strong cooperation with LATAM to better serve South America without necessitating it flying its own planes over there, plus it allows for a larger ‘local’ route network in South America by transferring its passengers onto domestic LATAM flights (and vice versa too, of course!). As such, these strategic investments can truly extend the ‘reach’ of an airline’s network. In Delta’s case the financial stake is important, because it puts Delta in a position where it can exert control over LATAM operations (e.g. flight schedules) to better suit its own needs.

More recent examples are:

- Air France/KLM acquiring a stake in SAS, which is the reason SAS subsequently left Star Alliance and joined SkyTeam. The idea is that SAS will join the transatlantic alliance with Delta, Virtgin Atlantic and Air France/KLM.

- On the other hand, Lufthansa group recently acquired a 19.9% stake in Italian operator ITA Airways (the follow-up to Alitalia), similarly hoping it will be able to join their own transatlantic alliance with United, Air Canada and Lufthansa Group’s set of airlines (Lufthansa, Brussels Airways, Austrian and Swiss).

Other airlines organize a network of partnerships without necessarily entering any kind of alliance, or acquiring any stakes. Emirates has not joined and alliances, but does have a strong partnership with United Airlines, for example, as well as myriad other airlines around the world.

Summary

In order to maximize the value of your points, it’s essential to be aware of who partners with who, so that you know what frequent flyer program can give you the best value for the flight you’re hoping to redeem for. There are three ‘tiers’ of partnerships, with the interline agreement being the most casual, then codeshares and finally joint ventures. Here, airlines align their schedules and pricing to tightly coordinate their operations. Alliances are a little different and I will delve into those at a later point.

Leave a comment